My name is Dylan, and I’m one of William Bell’s children, along with Megan and Brendan. I’m here to tell you the story of my Dad, from the perspective of his family, and I hope I can do them, and my father, justice.

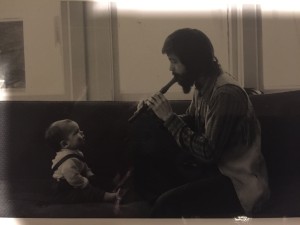

Dad grew up in working-class New Toronto, the son of a William, a tool-and-die maker, and Irene, a full-time homemaker. He went to Lakeshore Collegiate where he fell in love with literature, and with writing. He played clarinet in the school band, and was valedictorian of his graduating class. He also gave us the Bell tradition of “academic achievement,” which really meant excelling at the subjects you cared about, and kind-of skating through the stuff that didn’t matter to you. A fine start for a master educator.

Dad said that in his neighbourhood, your expected life path was pretty simple. You went to school until you were eighteen (if that), and went straight to work in one of the local factories, where you would stay until you retired. But Dad was never one to take the obvious path. Instead, he, and his sister Carole, fulfilled a dream their own father had, but never managed to achieve: they went to university, the first in their family to do so. Dad wrapped up the 1960s with two Bachelor degrees, and a Master of Arts. Later, he would add a Masters of Education to the list.

Also around this time, he met Susan Arnup, our mother. They married in 1970, and moved to Orillia, where Dad started his thirty-year teaching career, and where he became a father. I was born in 1972; Megan in 1973. Brendan joined us in 1980.

When we were little, Dad seemed larger than life: infallible, indestructible, and unquestionable. We looked on him with love, admiration, and maybe a little fear. Dad’s word was law. He was strict – maybe too strict, sometimes – but rarely unfair. His punishments came down not as wrath from the gods, but as Solomon-like consequences for your actions.

I still remember the first time I was caught stealing, at the age of six. We weren’t allowed candy in the house, so I took it upon myself to acquire some. In an uncharacteristic move, I offered to share some with my sister, who then, naturally, ratted me out to Dad. When he finally got the truth out of me, he didn’t get angry. He didn’t ground me. Instead, he simply marched me back to the store, parked me in front of a cashier, and said, quietly:

“My son has something he wants to say to you.”

I don’t think I ever went back to Miracle Mart without a deep sense of shame.

But sometimes he just let karma take its course. I was notorious for teasing my younger sister, but after years of one-sided torment, Megan finally learned how to tease back. When I went to complain, Dad said simply: “Don’t come to me. You deserve it.”

But for all his hard edges as a father, you could occasionally see the soft underside. He came across tough, but I still recall, even at a very young age, how it hurt him if his children were upset with him. His solution was to charm you, just enough for you to forget why you were angry in the first place. It pretty much always worked.

But the way he handled it with Megan became family legend. After some presumably-horrible injustice by Dad, Megan wrote him a letter. It said,

“Dad

I hat you.”

… to which Dad artfully responded:

“Megan… I glove you.”

Brendan got his turn, too. When he was about four, in the middle of a fight with Dad, he worked up the courage to talk back, using the strongest language he could come up with. But knowing that swearing was out of the question, he yelled “Dad, you’re full of… BULLY!” Dad stifled a giggle, and the phrase “fully of bully” stayed in the family lexicon for years.

Dad once told me that, as a kid, he felt he never measured up to his own father. His Dad, our Papa, was an old-school Irish working-class man of his generation. He rarely let his feelings show, especially in front of his kids. It was only when Dad was eighteen, working at his father’s factory, that he heard, second-hand, through his Dad’s co-workers, how proud his father was of him. But by then, Dad said, it was too late. He never entirely lost that feeling of not being good enough. Dad vowed never to let his children feel this way, and in this, he succeeded. He was never afraid to show us, and tell us, how proud he was of each of us.

There are endless stories of our childhood, but a few images stick out. The jungle-gym he built in our yard at 91 Neywash. The stoplight he lobbied the city for at the top of our block. Dad and Brendan watching car-races together. And of course, the family trip to the east coast.

Mom and Dad had an old Volkswagen van with the middle seat removed. Megan and I sat in the back, where we ate Oreos and peanut-butter cookies, listened to John Denver on the cassette deck, and tried to hold down the nausea from the smell of overheated seat-vinyl. Instead of a carseat, Dad rigged the seatbelts to hold a playpen, where a 1-year-old Brendan roamed free in a manner that would probably land Dad in jail for child-neglect today.

Dad was always curious, and this led to wanderlust. In 1982, Dad took a leave from his job as department head of Innisdale Secondary School, packed up the whole family, and took us to China for a year. It was a life-changing experience for all of us: from then on, we were unable to see the world in the same, small-town way. Brendan, who was two-going-on-three, was practically bilingual, and spoke Chinese better than any of us. I suppose it was the beginning of our journey as global citizens, and it was a big part of the lifelong learning that Dad gave to each of us.

It must have been around 1981 or so that I saw a single piece of paper on Dad’s typewriter, in his study where, up until recently, Brendan’s crib had been. Dad had created a fictional hospital-admissions form. This turned out to be the first page of his first novel, and the genesis of his career as an author. In between teaching, and raising three kids, and moving to China for a year, Dad would pick away at this for some time. He never really planned to do anything serious with it, until a 10-year-old Megan said:

“Dad, why don’t you get it published?”

So, Dad sent it around to various publishers, and finally in 1986, at the age of 41, Dad became a published author. He went on to write 15 young-adult novels, two picture-books, several essays, and a book of short stories. He won numerous awards, and while he (and we) were proud of his achievements, he never made a big fuss of them. In fact, I still remember the humble-yet-sardonic way he announced his induction into the Orillia Hall of Fame. He called me up and before announcing it, said:

“… are you sitting down?”

In 1985, we went to China a second time, this time to Beijing. While there, Dad met Ting-Xing Ye, and fell in love. In circumstances worthy of one of his novels, he managed to find a way to get Ting out from behind the bamboo curtain, and into Canada to stay. Ting joined our family over thirty years ago, and has been a loving and devoted wife to Dad ever since.

Around this time, Megan and I started high school. And typical of Dad, he wouldn’t stay far away, going so far as to start working at ODCVI again. If you think having your Dad stay up until you get home to ensure you made curfew was bad enough, try having him teach at your high school. It was…. challenging… at times. But, it meant that Megan and I had him as our teacher. And he was, far and away, the greatest and most inspiring teacher we’ve ever had. Even when he kicked us out of class.

Dad kept teaching, and writing. His kids grew older, and with it, his role as father – and our sense of our Dad – changed. I still remember the moment I felt that change. I was nineteen, and went to a cast party for a play. I stumbled home at 7am, safely assuming that Dad would be asleep when I got home. No such luck. Dad was up early, watching one of his car races on TV. I mumbled something and went to bed, anxious to see what punishment awaited me when I woke up. And apart from the stony silence of unspoken disapproval, there was none. It had hit us both: I was an adult, and his job as disciplinarian was over.

And that’s when I realized that’s what it was: Dad’s job. All the strictness and discipline, the impatience and occasional exasperation, stemmed from what Dad felt he needed to do, in order to be a good father. And gradually, over the years, we became friends.

But while his role as parent changed, he never stopped being our father. He was our centre, our source of strength. He taught us right from wrong; he instilled in us the importance of independent, critical thinking, of compassion and ethical thought and action. He gave us the moral compass which we each hold and carry, and which Megan passes to her children every day. His guidance was so strong that, on occasion, it made it hard for us to find our own way. It was hard to miss the hints he would drop – for years, he would give us University of Toronto T-shirts, and mugs, and just about anything else – but when we did find our own way, even if it wasn’t what he had imagined, he was proud of each of us.

But beyond all this, and most importantly, he was simply there. And that was the greatest gift he gave us: his presence. He always stayed with us, even when life circumstances, or changes in our family dynamic, made it difficult. He never gave up, because in our family, you’re always there.

And that extended beyond his children, and onto those his children love. Ask my wife Suba, or Brendan’s partner Irene, Megan’s partner Jake. To Dad, they were treated like sons and daughters.

By 1999, Dad decided he had had enough of the Common Sense Revolution and its attack on teachers, and chose early retirement. But he didn’t stop working, and refused to say he’d retired. He “quit teaching,” and spent more time writing. And a few years later, Dad had a new job: Papa.

When his daughter became a mother, Dad wrote her this:

“I have waited a long time to say this: I have loved you every second of your life since the day you were born. Now that you have a little girl of your own, you’ll know how much.”

That little girl was Bella, and she was followed by his two grandsons, William and Seamus.

Dad continued to write and spend time with his family. He and Ting built a beautiful cottage on Rollo Bay in PEI, and they became honourary summer Islanders, along with Bob Gauldie and Lynne Murray, and Bill and Alison Talbot. He travelled frequently, including trips to China to visit Ting’s family, her daughter Qi Meng, and her granddaughter Lin Jiahan, the Little Panda . He created beautiful woodwork, which still graces our homes. He had dinners with friends and family, including his and Ting’s locally-famous annual Chinese New Year’s celebration.

And on September 10 last year, while Dad was in PEI, he got the news: a likely diagnosis of cancer, and he was ordered to fly to Toronto, and check into Princess Margaret Hospital, first thing in the morning. There, They confirmed the worst fears: advanced leukemia.

For ten months, Dad fought, and he fought hard. He had ups and downs, little victories and setbacks. And no-one fought harder for him than Ting… not even himself. She’s a fighter too, and gave him a level of care and undying support that only a life partner can give. We should all hope to have someone as tirelessly devoted, so tenacious and strong, fighting in our corner. Ting, he never would have made it this far without you.

In the end, he got what he wanted: he spent his last days surrounded by family, day and night, and on Saturday, July 30, he breathed his last.

* * *

People always say that those who die never leave us, that they exist in our hearts and in our memories. But it’s far, far more than that. For those of us who are his family… he is in us, literally. He is in our blood, our bones, our DNA, our spirits and our souls. He continues to make himself known, through each of us.

Carole: you’re Dad’s “Irish twin,” and in that sibling-way, I see you as his other half. Whenever I look into your eyes, I’ll see Dad twinkling back.

Megan: I see Dad in your solid sense of right-and-wrong, and the mindful and loving way you raise your children to be smart, aware, thinking and feeling human beings. I also see Dad’s intolerance for bullshit!

Brendan: I see Dad in your constant quest for self-development and enlightenment, and in the passion and sensitivity burning inside you, just beneath the surface. I think you also got most of his good looks.

Bella: I see your Papa in your emotional intelligence, your ethics and principles, and your firm resolve to be yourself, even when it’s hard sometimes.

William: I see your Papa in your problem-solving, crazy-curious brain, and your kindness and thoughtfulness to other people. And, if I may say so, your stubbornness!

Seamus: I think Papa was probably a lot like you when he was a kid: quiet and thoughtful. But underneath that quiet is a whole lot of secret power: I hope you see it as much as we do. Also, you do Papa’s eyebrow thing pretty well.

Brendan summed it up beautifully, in saying:

“Where does my Dad end and where do I begin. When I see his image, I see can see myself. When I speak, sometimes I hear his voice. I miss him so much and he will be with me always.”

* * *

A couple of years ago, Dad said to me: “I was thinking of writing my memoir. But then I thought… who would want to read it?” Well, Dad, look around you. Look at all the people here, your loved ones, your friends, and your colleagues. Think of the thousands of students whose lives you shaped over your thirty years of teaching. Think of the thousands more who read your novels. I think I can speak for all of us and say: if you had indeed written it, we would have read it cover to cover.

And it would have been a masterpiece.

We are grateful to The Princes Margaret Cancer Care Centre, and Hospice Simcoe, for the incredible care they gave my father. Please consider making a donation to these worthy organizations.